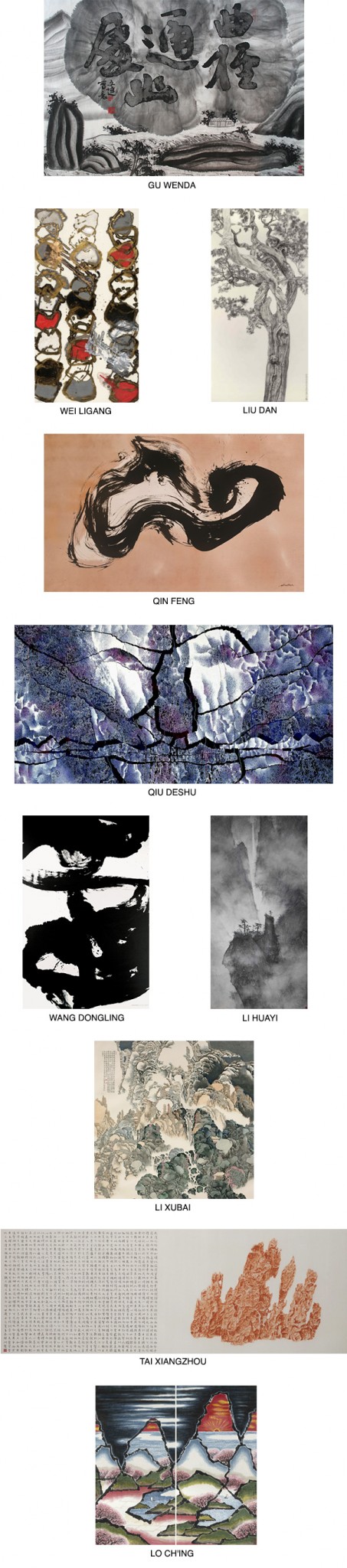

Chinese Contemporary Ink Art: Ten Leading Artists

Presented by Michael Goedhuis

Presented by Michael Goedhuis

Michael Goedhuis will be exhibiting the ten best contemporary ink painters from China.

The exhibition will describe, through the works of these ten leading artists, how Chinese contemporary culture is being transformed via a profound understanding of Chinese historical civilization. Gu Wenda, Li Huayi, Li Xubai, Liu Dan, Lo Ch’ing, Qin Feng, Qiu Deshu, Tai Xiangzhou, Wang Dongling and Wei Ligang are creating a new pictorial language which expresses the fundamentals of Chinese aesthetics and culture in ways which are relevant to today’s society in China and also to the developments in the West.

Ink paintings emerged 1000 years ago from calligraphy: the sublime and central achievement of China. Calligraphy is executed in ink on silk or paper, with a brush. In order to master this brush on the absorbent paper, which tolerates no error or correction, the artist has to achieve a high degree of concentration, balance and control. Painting is an extension of the art of calligraphy. It is therefore, like calligraphy, linked to the sacred prestige of the written word.

It has been almost impossible until recently for westerners to grasp the significance of calligraphy for the Chinese. It has been the foundation-stone of their society since the dawn of civilization. It is the most elite of all arts…practiced by emperors, aesthetes, monks and poets throughout history but also ostentatiously alive today in advertisements, cinema posters, restaurants, tea-houses, railway stations, temples and on rough peasant village doors and walls.

Ink painting was practiced by the scholar gentleman for whom the prime purpose is the cultivation of an inner life, the ultimate aim of which is to perfect one’s character in order to attain the moral stature befitting one’s status as a gentleman.

Contemporary Literati Art: Ink Art

The successors of the gentleman-scholars described above are today’s ink artists. They are deeply aware of the classical canon and its aesthetic and moral imperatives and have carefully studied the old masters. However, just as Picasso and Cezanne studied Raphael, Poussin, Velasquez and others in order to create THEIR revolutionary pictorial language, so the new literati are doing the same in order to formulate their own revolution for their work to be relevant to, and meaningful for, the world of today. And revolutionary and culturally subversive it is. More subtle than the contemporary oil painters with their abrasive handling of overtly political themes, the ink painters embody their revolutionary message in works that are not afraid to take account of the past in order to make sense of the present.

Very many different stylistic approaches have therefore evolved over the past 30 years. Works now range from those that at first sight look quite traditional but in fact embody powerful fresh aesthetic initiatives by artists like Liu Dan, Li Xubai, Li Huayi, Yang Yanping, to those that are unambiguously avant-garde seen in the works of Qiu Deshu, Wei Ligang, Yao Jui-chung, Lo Ch’ing, Wang Dongling and Gu Wenda.

It is therefore probable that these few (only 50 or so of international stature) artists are poised to assume a historic relevance as the cultural conduit between China’s great past and her future. And as such they are likely to shortly become the target of the new generation of collectors and museums in China and the diaspora who, in their newfound national pride and following the global fashion that only contemporary is cool, will be hungry for contemporary manifestations of their country’s enduring civilization.

Michael Goedhuis, who was the first dealer in the west to recognize the significance of these radical innovations in Chinese culture, has concentrated on identifying the artists who are in the process of shifting the axis of Chinese aesthetics.

In 2008, he assembled and curated the major contemporary Chinese Art collection, the Estella collection, which was exhibited at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Most of his activity since then has been directed at describing both the resurgence of cultural activity in the China of today and the key relevance of Chinese Ink art to contemporary aesthetics.

The exhibition will describe, through the works of these ten leading artists, how Chinese contemporary culture is being transformed via a profound understanding of Chinese historical civilization. Gu Wenda, Li Huayi, Li Xubai, Liu Dan, Lo Ch’ing, Qin Feng, Qiu Deshu, Tai Xiangzhou, Wang Dongling and Wei Ligang are creating a new pictorial language which expresses the fundamentals of Chinese aesthetics and culture in ways which are relevant to today’s society in China and also to the developments in the West.

Ink paintings emerged 1000 years ago from calligraphy: the sublime and central achievement of China. Calligraphy is executed in ink on silk or paper, with a brush. In order to master this brush on the absorbent paper, which tolerates no error or correction, the artist has to achieve a high degree of concentration, balance and control. Painting is an extension of the art of calligraphy. It is therefore, like calligraphy, linked to the sacred prestige of the written word.

It has been almost impossible until recently for westerners to grasp the significance of calligraphy for the Chinese. It has been the foundation-stone of their society since the dawn of civilization. It is the most elite of all arts…practiced by emperors, aesthetes, monks and poets throughout history but also ostentatiously alive today in advertisements, cinema posters, restaurants, tea-houses, railway stations, temples and on rough peasant village doors and walls.

Ink painting was practiced by the scholar gentleman for whom the prime purpose is the cultivation of an inner life, the ultimate aim of which is to perfect one’s character in order to attain the moral stature befitting one’s status as a gentleman.

Contemporary Literati Art: Ink Art

The successors of the gentleman-scholars described above are today’s ink artists. They are deeply aware of the classical canon and its aesthetic and moral imperatives and have carefully studied the old masters. However, just as Picasso and Cezanne studied Raphael, Poussin, Velasquez and others in order to create THEIR revolutionary pictorial language, so the new literati are doing the same in order to formulate their own revolution for their work to be relevant to, and meaningful for, the world of today. And revolutionary and culturally subversive it is. More subtle than the contemporary oil painters with their abrasive handling of overtly political themes, the ink painters embody their revolutionary message in works that are not afraid to take account of the past in order to make sense of the present.

Very many different stylistic approaches have therefore evolved over the past 30 years. Works now range from those that at first sight look quite traditional but in fact embody powerful fresh aesthetic initiatives by artists like Liu Dan, Li Xubai, Li Huayi, Yang Yanping, to those that are unambiguously avant-garde seen in the works of Qiu Deshu, Wei Ligang, Yao Jui-chung, Lo Ch’ing, Wang Dongling and Gu Wenda.

It is therefore probable that these few (only 50 or so of international stature) artists are poised to assume a historic relevance as the cultural conduit between China’s great past and her future. And as such they are likely to shortly become the target of the new generation of collectors and museums in China and the diaspora who, in their newfound national pride and following the global fashion that only contemporary is cool, will be hungry for contemporary manifestations of their country’s enduring civilization.

Michael Goedhuis, who was the first dealer in the west to recognize the significance of these radical innovations in Chinese culture, has concentrated on identifying the artists who are in the process of shifting the axis of Chinese aesthetics.

In 2008, he assembled and curated the major contemporary Chinese Art collection, the Estella collection, which was exhibited at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Most of his activity since then has been directed at describing both the resurgence of cultural activity in the China of today and the key relevance of Chinese Ink art to contemporary aesthetics.

Back